Explore how securitization is transforming financial markets — turning everyday loans into powerful investment tools. This whitepaper breaks down the process, products, and post-crisis reforms that are creating smarter, safer opportunities for today’s investors.

Executive Summary:

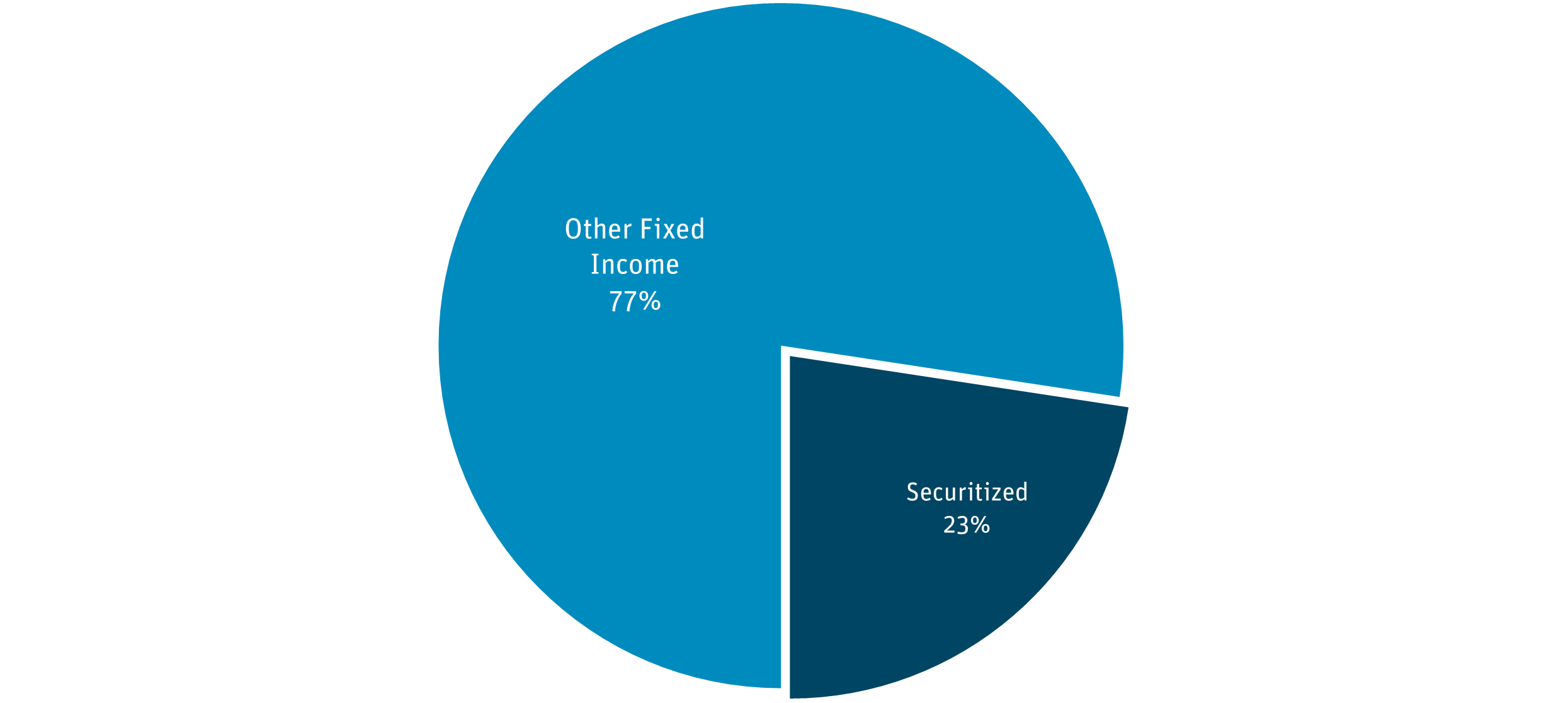

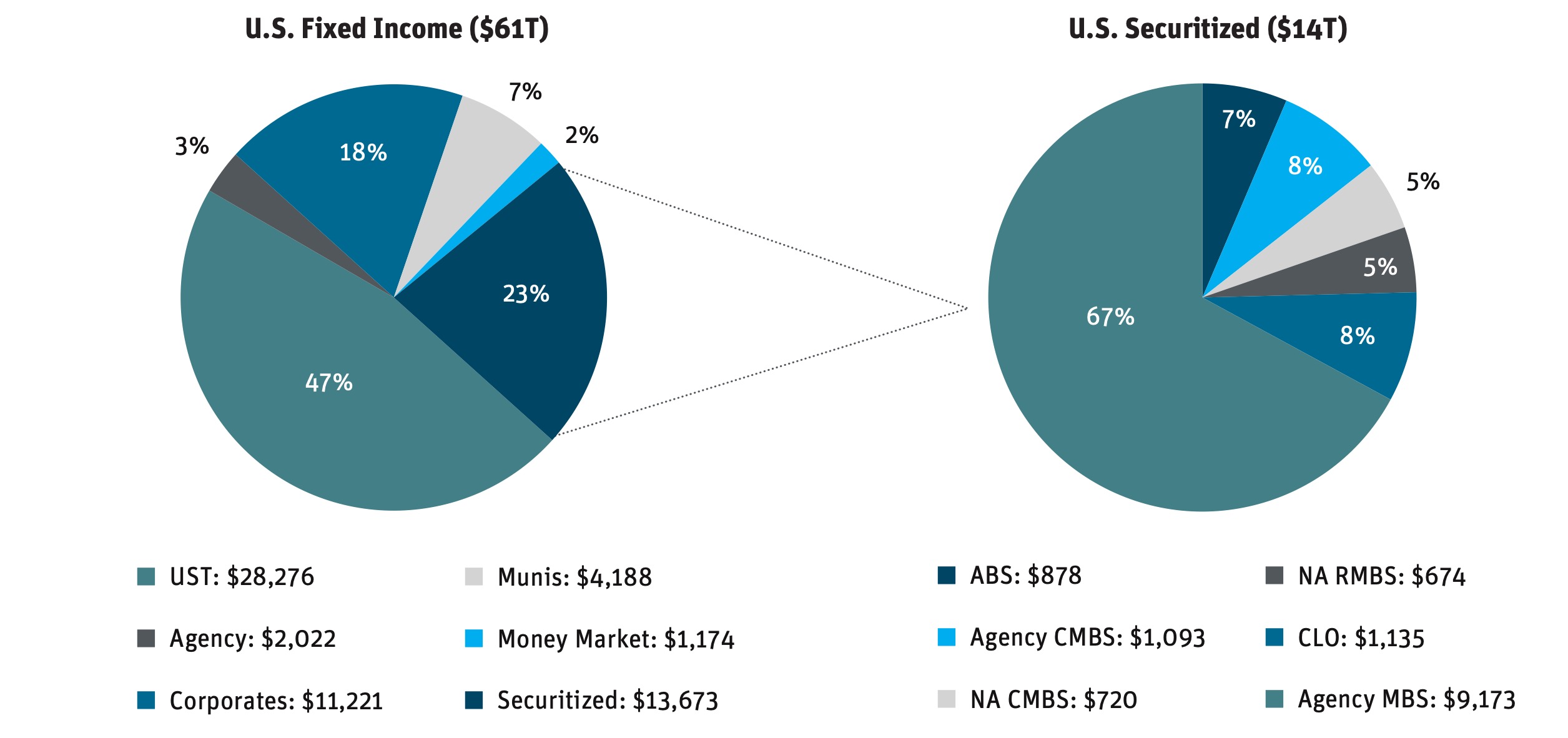

- Securitization (Structured Finance) – The process of transforming illiquid assets (e.g., mortgages and other loans/leases) into tradable securities, enhancing funding, liquidity, and investor access. It supports credit generation by attracting funding from the capital markets to lenders, enabling more lending than they could otherwise fund from their balance sheets. Securitized products comprise almost a quarter of the U.S. fixed income markets.

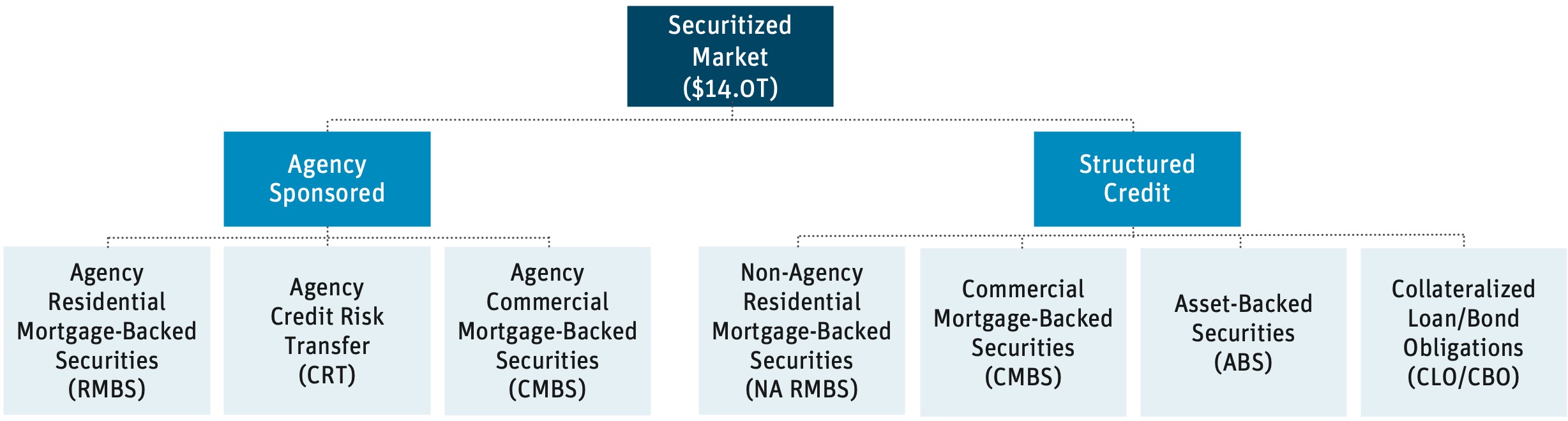

- Market Segmentation – Agency-sponsored products (e.g., Agency RMBS/CMBS, CMOs, CRTs) are fully or partially guaranteed by the government (Ginnie Mae, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac), offering strong credit stability but exposure to prepayment and interest rate risks. Private Label/Non-Agency products (e.g., Non-Agency RMBS/CMBS, ABS, and CLOs) offer higher yield and flexibility but carry greater credit and liquidity risks due to lack of government backing.

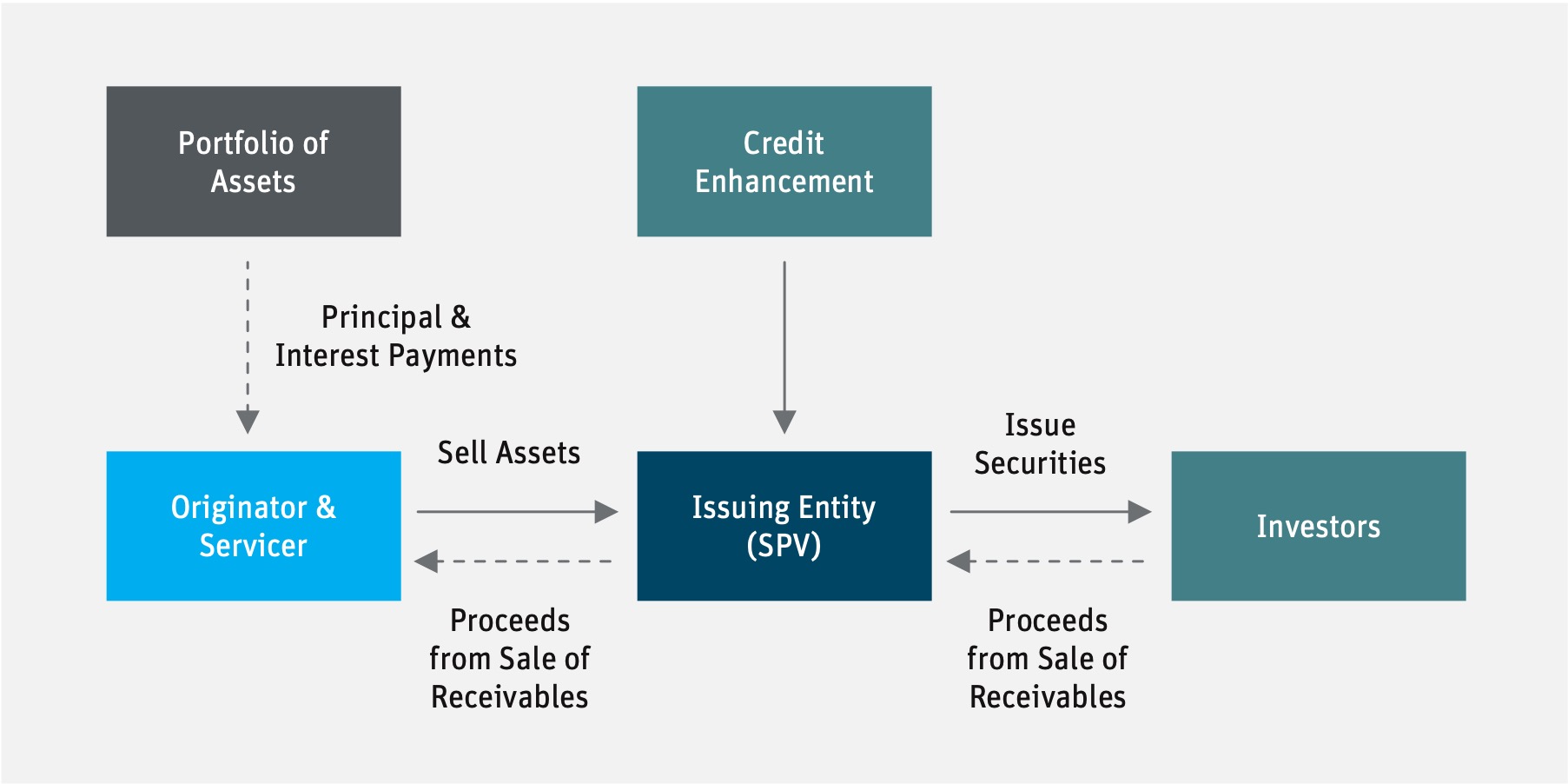

- Process – Key steps include loan origination, pooling assets into special purpose vehicles (SPVs), and issuance with credit enhancements like cash flow prioritization, overcollateralization, reserve accounts, and senior-sub structures. These mitigations address liquidity, prepayment (negative convexity), and credit exposure, tailoring risk for different investor risk appetites.

- Market Evolution and Investment Opportunity – Post-global financial crisis (GFC) reforms (e.g., Dodd-Frank risk retention rules and Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) oversight) have made securitized markets safer. Despite their complexity, these products offer attractive risk-adjusted returns, especially for informed investors willing to navigate their unique risks and structural features.

U.S. Fixed Income ($61T)

Source: SIFMA as of 4/30/25.

I – Introduction to Securitization

Securitization, also known as “structured finance,” is a crucial component of the capital markets that enables institutions to transform a wide range of assets, which might otherwise be difficult to trade individually, into marketable securities. This process raises funding for ongoing credit generation while also providing liquidity and tailored opportunities for a broad range of investors. This primer explores the structure, size, and mechanisms of the market, as well as the key factors that distinguish the different securitized asset classes.

II – Market Structure

Source: BAML as of 4/30/25.

Agency-Sponsored Products

- Residential Mortgage-Backed Securities – Introduced in the late 1960s when Ginnie Mae (a true government agency) issued the first mortgage-backed security. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) and began issuing “Agency” RMBS soon afterward. Agency RMBS are fully guaranteed by the U.S. Treasury.

- Agency pass-throughs (Agency MBS) provide a pro rata share of principal and interest payments to investors in proportion to the size of their investment.

- Agency collateralized mortgage obligations (Agency CMOs) are structured securities that reallocate the principal and interest (P&I) of an existing pass-through Agency RMBS to investors based on specific rules. The most common Agency CMO structure is a sequential-pay bond that allocates principal to investors in a specific sequence so certain investors are paid off early while others are paid off later.

Key Benefits |

Key Risks |

|---|---|

|

|

- Credit Risk Transfer (CRT) Bonds – Fannie Mae’s Connecticut Avenue Securities (CAS) program and Freddie Mac’s Structured Agency Credit Risk (STACR) program are securitized products where the issuers transfer a portion of the credit risk of their guaranteed mortgage portfolios to private investors. This initiative, which began in earnest after the 2008 financial crisis, aims to build a more robust housing finance system that is less reliant on government support during periods of stress.

Key Benefits |

Key Risks |

|---|---|

|

|

- Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities (Agency CMBS) – First issued by Fannie Mae (DUS) program in the late 1980s and Freddie Mac (K-Series) in 2009, providing a mechanism to finance multifamily housing and healthcare-related properties like hospitals and clinics. The senior tranches of these securitizations are generally guaranteed by Fannie or Freddie, while investors in the more subordinated tranches can bear some degree of credit risk depending on the structure of each deal.

Key Benefits |

Key Risks |

|---|---|

|

|

Note: While Agency-sponsored securitized bonds are currently fully or partially guaranteed by the U.S. Treasury, it is possible that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac might be privatized at some point in the future, at which time subsequent issues guaranteed by those entities could lose some or all of the government guarantee.

Structured Credit (Non-Agency or Private Label) Products

- Residential Mortgage-Backed Securities (NA RMBS or PL RMBS) – Emerged in the late 1980s, allowing non-Agency lenders to securitize residential mortgages. This market expanded significantly through the 2000s, enabling a broader range of mortgage structures for borrowers with less conventional income sources to be financed through the capital markets.

Key Benefits |

Key Risks |

|---|---|

|

|

- Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities (CMBS) – First issued in the 1990s, gained traction as a way to finance commercial real estate portfolios. Unlike Agency CMBS, these “private label” deals are structured by investment banks and lack a government guarantee, tying their credit performance directly to the underlying commercial property loans.

Key Benefits |

Key Risks |

|---|---|

|

|

- Asset-Backed Securities (ABS) – Developed in the 1980s, with early issuances backed by auto loans and credit card receivables. The growth of this sector has allowed for the securitization of a wide array of consumer debt, from student loans and personal loans to equipment leases and even timeshare payments. There has recently been growth in commercial ABS, which tends to be a catchall for corporate ABS bonds that are not backed by mortgages. Common types are data center ABS, franchise receivables ABS, aircraft ABS, and equipment ABS.

Key Benefits |

Key Risks |

|---|---|

|

|

- Commercial Loan/Bond Securitizations – Collateralized Loan Obligations (CLOs), which originated in the late 1980s and focused on corporate loans made to below investment grade borrowers, as well as Collateralized Bond Obligations (CBOs), which are securitizations of high-yield bonds with issuer and industry diversification. CLOs have become a cornerstone of the leveraged finance market, providing a highly standardized, structured, and liquid market for institutional investors to access exposure to syndicated corporate loans.

Key Benefits |

Key Risks |

|---|---|

|

|

III – Market Data

Source: BAML as of 4/30/25.

IV – Securitization Process

- Loan Origination: A lender (e.g., bank, mortgage company, or auto finance firm) underwrites and issues loans for individuals or businesses, generating contractual cash flows that serve as the basis for securitization.

- Asset Pooling & Securitization: These loans are pooled and acquired by a special purpose vehicle/entity (SPV/SPE), which raises capital through the issuance of debt and residual interest securities, collectively known as asset-backed securities.

- Note: The acronym “ABS” is usually specifically used to describe securitizations of consumer (auto, credit card) and esoteric (data center, aircraft lease) assets.

- Collateral Requirements: Securitized assets must carry contractual payment obligations and involve a payer (borrower, lessee, insurer, etc.) and a contract type (mortgage, lease, loan, or accounts receivable).

- Asset Homogeneity: Securitizations typically group assets with similar characteristics—for instance, auto ABS contain exclusively auto loans or leases with comparable coupon rates and maturities, while residential MBS comprise residential mortgage loans with similar terms.

- Structural Safeguards: Securitization structures are designed to protect investors from losses and cash flow volatility by utilizing some combination of the following:

- Waterfall Structure: Defines cash flow allocation to various classes of investors, which might include triggers for early payoffs if collateral performance deteriorates.

- Overcollateralization: Collateral value exceeds bond principal value, providing a buffer against losses—defaults or declines must surpass a threshold before bondholders incur principal losses.

- Diversification: Geographic and borrower diversity minimizes collateral correlation risk.

- Excess Interest: Surplus interest from collateral can be used to fund a reserve account and is the first line of defense against collateral losses.

- No Recourse/Bankruptcy Remoteness: The issuer cannot reclaim assets from the SPV in cases of financial distress or bankruptcy.

- De-Leveraging: Risk reduces over time as principal amortizes down.

- Special Servicing: Servicers can advance payments on delinquent loans to maintain P&I cash flow stability.

Benefits of Securitization:

-

- Enhanced Liquidity: Securitization transforms illiquid assets into liquid securities, broadening investor appeal.

- Diversified Funding Sources: Bank originators gain capital markets access, reducing reliance on traditional deposits and expanding lending capacity.

- Match Funding: Securitization terms out financing so the underlying loan duration matches liabilities.

- Risk Transfer: Securitization allows issuers to effectively shift the credit and interest rate risk associated with the securitized assets away from their own balance sheets and to investors who want to assume that risk; lenders can free up capital and reduce regulatory capital.

- Lower Funding Costs: Securitizing assets can achieve a lower overall cost of funding for corporate issuers compared with issuing debt or equity directly.

- Investor Choice: Investors can gain access to new asset classes, enhance return potential, and select tranches with tailored risk/return profiles.

- CLO Arbitrage: Many managers issue CLOs because the securitization mechanism itself presents a significant arbitrage opportunity. They aim to construct a portfolio of higher-yielding leveraged loans and fund it with different tranches of CLO debt, which has a lower weighted average cost of capital, thereby generating a profitable spread for equity investors and management fees.

Higher Yields in Securitized Credit Tend to Exist Due to These Common Risks:

Liquidity Risk – Securitized products can be less liquid (compared with Treasuries, agencies, and corporate debt) due to their complexity and the unique characteristics of their underlying collateral. Since 2008, securitizations have become more standardized. Government guarantees and investor-friendly cash flow structures help ensure that the primary and secondary markets for securitized products remain active, reducing bid/ask spreads and increasing liquidity. There are various levels of liquidity across structured finance, and many issuers, sectors, and asset classes vary in levels of liquidity over time.

Prepayment Risk – Many securitizations have collateral (mortgages, consumer loans, auto loans) that grant borrowers the option to prepay their loan in whole or in part before maturity. These prepayment risks/options can be at the deal and collateral levels. This option is most often exercised when market rates decline and borrowers can refinance at more favorable levels. Investors receive principal earlier than expected, shortening the weighted average life of the securities (“contraction risk”). This principal will then be reinvested at lower market rates, reducing returns. Conversely, borrowers are less likely to exercise their prepayment option when market rates rise, lengthening the weighted average life of the security (“extension risk”) and locking the investor in at a rate that is now lower than market rates. The adverse outcomes associated with prepayment risk are also referred to as “negative convexity,” (see Negative Convexity & Opportunities in the Mortgage Market whitepaper for more) and securitized bonds often incorporate structures that reallocate cash flows or limit prepayment options to mitigate this convexity risk.

Credit Risk – With the exception of Agency-guaranteed MBS, most securitized bonds expose investors to some degree of credit risk, generally in the form of delinquencies and defaults on the underlying loan collateral. This risk can be mitigated within a senior-subordination structure where senior bondholders are protected against risk by investors in the more junior tranches in the transaction. Defaults (after any recoveries on the underlying collateral) are allocated to junior bondholders in a structural hierarchy. Credit enhancement can also take the form of reserve accounts funded from excess spread, overcollateralization, and third-party guarantees such as credit default swaps.

Common Transaction Structures Used to Mitigate Risks:

The following are the most common examples of structures that have evolved to manage the risks associated with securitized assets to ensure that investors are able to access the cash flow and return profile that fit their risk appetite:

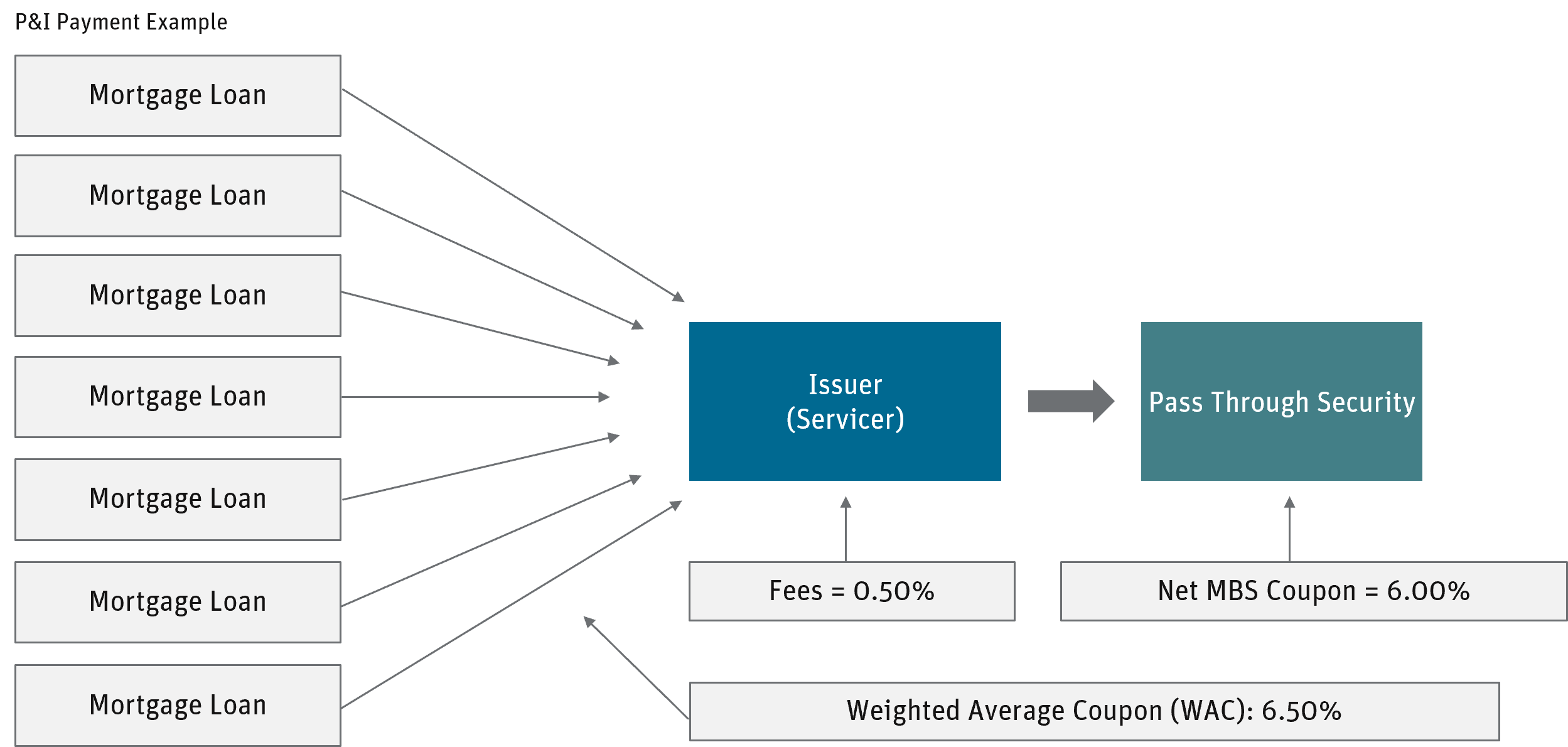

- Pass-through securities are structured so that the principal and interest from the underlying pool of assets are passed directly to investors. These securities do not involve a complex payment structure, meaning all investors receive proportional payments (“pari passu”) based on their ownership share. Pass-through structures are most frequently utilized in the Agency RMBS market, where credit risk is eliminated through a government guarantee. However, Agency RMBS are exposed to prepayment risk, as borrowers paying off loans earlier or later than expected can alter the timing of principal and interest cash flows and returns.

Pass-Through Securities (P&I Payment Example)

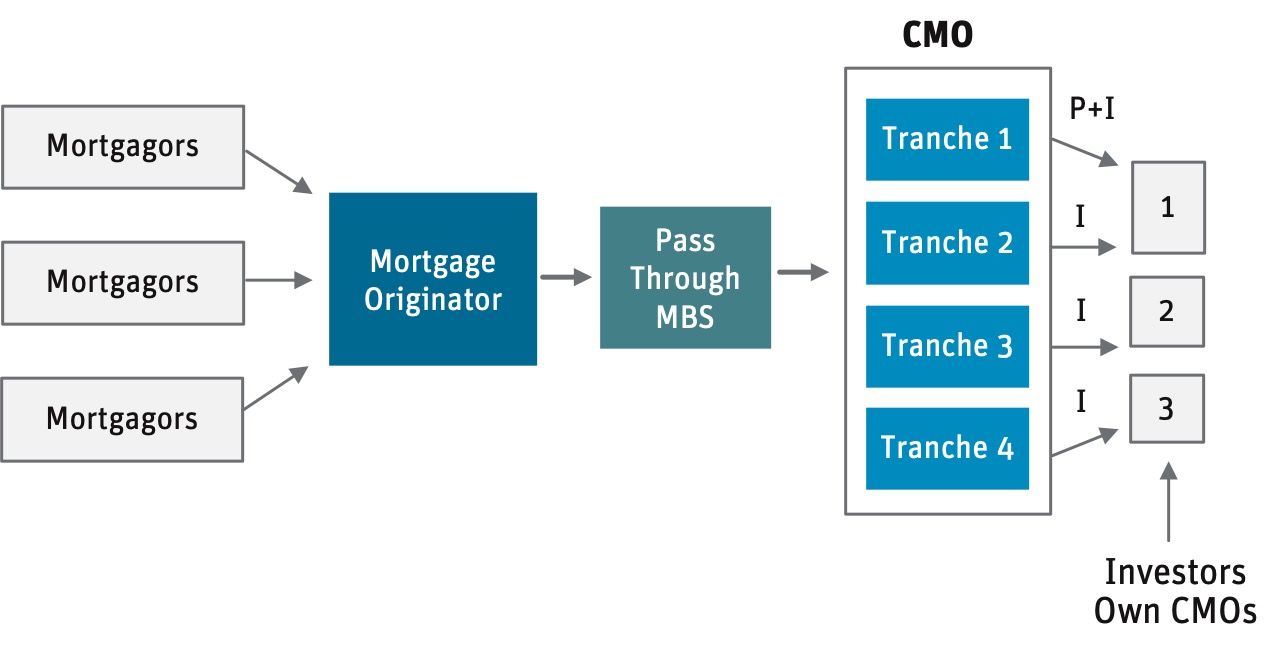

- Sequential-pay securities prioritize the order in which principal payments are allocated. Investors holding fast-pay tranches (like Tranche 1 below) receive principal payments first, while slower-pay tranches do not receive any principal until the preceding ones are paid in full. This structure allows different classes of investors to have varying degrees of risk exposure, with fast-pay tranches typically having shorter durations and a correspondingly lower yield profile. Sequential-pay bonds are generally more predictable in terms of P&I and prepayment risk, making them popular among investors who seek stable cash flows, and are found in both Agency-guaranteed and Non-Agency securitizations.

Cash Flows of a CMO

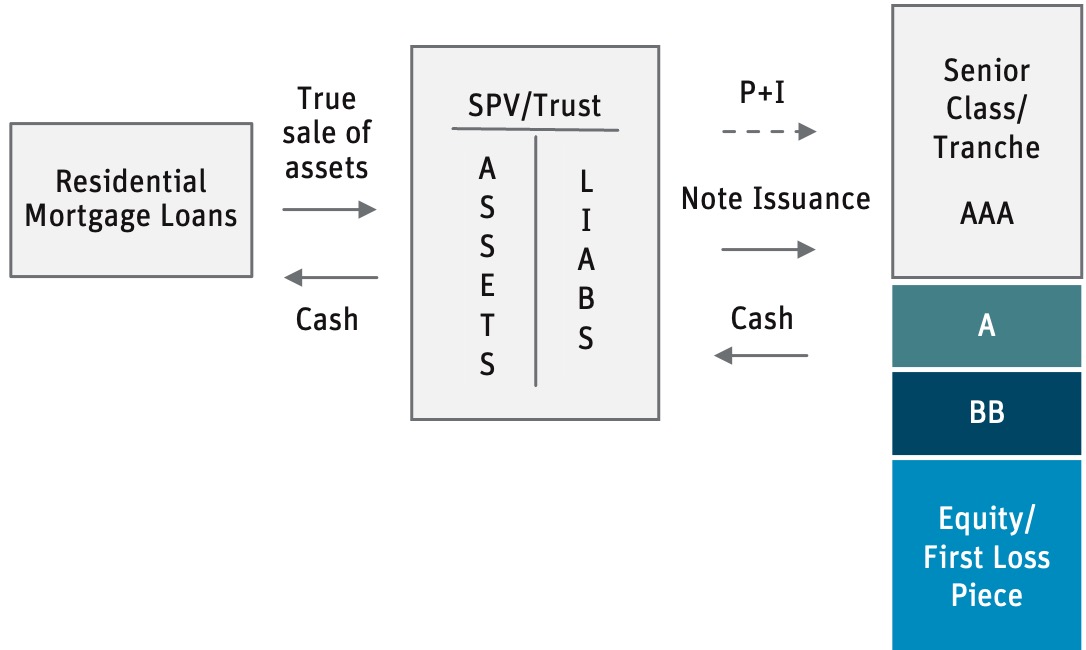

- Senior-subordination structures introduce a credit enhancement mechanism in which senior tranches receive principal and interest payments in priority to more subordinated (“junior” or “mezzanine”) tranches, which absorb losses in the event of collateral defaults. This prioritization makes senior tranches more attractive to risk-averse investors, while subordinated tranches offer higher returns due to their increased exposure to credit risk. A subset of Agency RMBS called CRT securities utilize senior-subordination structures to partially transfer limited credit risk in these bonds to investors, but this structure is most frequently used in the non-Agency segments of the securitization markets.

RMBS: Credit Tranche/Class

V – Opportunities in Securitized Products

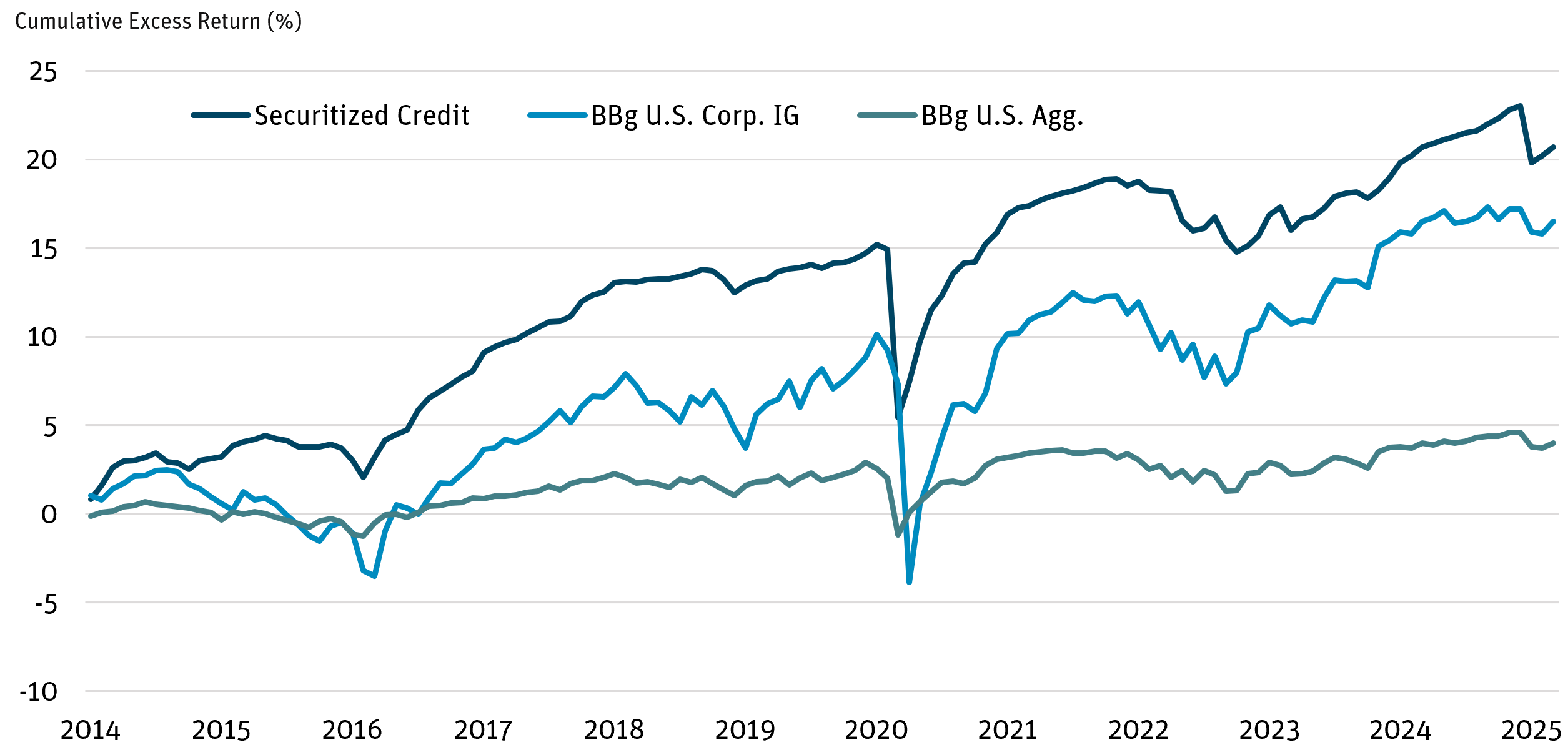

Securitized credit tends to earn a premium relative to corporate credit over market cycles. This premium can vary over time, and investors may have to hold through the credit cycle to harvest the premium.

Securitized Credit Has Historically Outperformed Corporate Credit

Source: BofA Global Research as of 5/31/25.

Past performance is not a guarantee of future results.

There are several potential drivers of the securitized credit premium, including:

- Recency Bias: The price volatility, rating downgrades, and credit losses experienced by some securitized products during the GFC still haunt some credit investors.

- Off Benchmark: Lack of representation in fixed income indices, such as the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index, which causes a liquidity premium.

- Complexity Premium: The complexity of the underlying structures causes less sophisticated investors to potentially shy away from the securities.

- De-Leveraging: Securitized credit securities are often collateralized by assets that are amortizing (e.g., mortgages, auto loans), unlike more traditional fixed income instruments with bullet structures that pay off all principal at maturity.

These factors are fundamentally technical in nature and not related to the underlying credit quality of the collateral assets providing the cash flows to investors. In addition, the risk of investing in securitized products has decreased since the GFC due to increasing regulation:

- The Dodd-Frank Act (the DFA, passed in 2010) contained risk retention requirements that significantly enhanced the safety of the RMBS market by requiring issuers to retain a first loss portion in many securitizations. This “skin in the game” incentivized originators and issuers to maintain higher underwriting standards, reducing the likelihood of future widespread defaults.

- The DFA also contained ability-to-repay (ATR) provisions in mortgage lending, which require lenders to make a reasonable and good faith determination of a borrower’s ability to repay a mortgage loan before extending credit.

- The CFPB was created to protect consumers from predatory lending practices by enforcing regulations, investigating complaints, and acting against lenders that engage in deceptive or abusive behavior against borrowers.

Taken together, we believe these factors have resulted in a dislocation in securitized markets that has created an attractive risk-adjusted return opportunity for investors.

DISCLOSURES

Agency: Refers to securities, either direct debt obligations or pools of mortgage loans, that are issued or guaranteed by government-sponsored enterprises like Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, or Ginnie Mae.

Asset-Backed Securities (ABS): Securities created by buying and bundling loans—such as residential mortgage loans, commercial loans or student loans—and creating securities backed by those assets, which are then sold to investors.

Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index: An unmanaged index that measures the performance of the investment-grade universe of bonds issued in the United States. The index includes institutionally traded U.S. Treasury, government sponsored, mortgage and corporate securities.

Bloomberg U.S. Corporate Investment Grade Index: An index that measures the investment grade, fixed-rate, taxable corporate bond market. It includes USD-denominated securities publicly issued by U.S. and non-U.S. industrial, utility and financial issuers.

Cash Flow: The net amount of cash and cash-equivalents being transferred into and out of a business, especially as affecting liquidity.

Collateralized Loan Obligation (CLO): A single security backed by a pool of debt.

Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities (CMBS): Fixed-income investments backed by mortgages on commercial properties rather than residential real estate.

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB): A regulatory agency charged with overseeing financial products and services that are offered to consumers.

Convexity: A measure of the yield curve in the relationship between a bond’s price and a bond’s yield.

Credit Risk Transfer (CRT): Programs that structure mortgage credit risk into securities and (re)insurance offerings, transferring credit risk exposure from U.S taxpayers to private capital.

Dodd-Frank Act: Commonly known as Dodd-Frank, this legislation was passed by the U.S. Congress in 2010 in response to financial industry behavior that led to the great financial crisis of 2007-08. Dodd-Frank was enacted to reduce systemic risk, increase transparency, and promote market integrity within the financial system.

Mortgage-Backed Security (MBS): A type of asset-backed security which is secured by a mortgage or collection of mortgages.

Non-Agency: Mortgage-backed securities issued by private institutions that are not backed by government-sponsored enterprises or the U.S. Treasury.

Prepayment Risk: The uncertainty of cash flows or potential loss faced by an investor in an asset-backed security when borrowers repay their loans or debts earlier than expected, which can affect the expected return on investment.

Residential Mortgage-Backed Securities (RMBS): Fixed income securities with cash flows that are collateralized by residential mortgages.

Spread: The difference in yield between two bonds of similar maturity but different credit quality.

Tranche: A portion of debt or structured financing. Each portion, or tranche, is one of several related securities offered at the same time but with different risks, rewards, and maturities.

Weighted Average Coupon (WAC): The weighted average of the underlying coupon interest rates of mortgage loans using the balance of each mortgage as the weighting factor.

Weighted Average Life (WAL): Average length of time that each dollar of unpaid principal on a loan, a mortgage or an amortizing bond remains outstanding.

The Securitized Products Return Indicator aggregates monthly return performance across the U.S. securitized products credit markets that Bank of America tracks into one number for both total return and excess swap return. The Agency MBS market is not included in the Indicator as it is focused on the return of non-guaranteed securities. There are two subsets of the indicator: 1) a AAA Indicator that tracks AAA-rated structured credit bonds and 2) a Down in Credit Indicator which tracks CLO BBB/BB tranches, CMBS BBB tranches and CAS/STACR below investment-grade rated bonds. The return data is weighted by the 1-month lagged outstanding par value of each indicator constituent. This methodology also applies to the two subset indicators.

Opinions expressed are as of 5/31/25 and are subject to change at any time, are not guaranteed, and should not be considered investment advice.

Investing involves risk; principal loss is possible. Investments in debt securities typically decrease when interest rates rise. This risk is usually greater for longer-term debt securities. Investments in lower-rated and nonrated securities present a greater risk of loss to principal and iCredit Risk Exposure: Unlike traditional Agency MBS, CRT bonds expose investors to the risk of borrower defaults, as they are designed to transfer mortgage credit risk away from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Prepayment Risk: Borrowers refinancing loans unexpectedly can impact yield. Interest Rate Sensitivity: Valuations fluctuate with rate movements. nterest than do higher-rated securities. Investments in asset-backed and mortgage-backed securities include additional risks that investors should be aware of, including credit risk, prepayment risk, possible illiquidity and default, as well as increased susceptibility to adverse economic developments. Derivatives involve risks different from — and in certain cases, greater than — the risks presented by more traditional investments. Derivatives may involve certain costs and risks such as illiquidity, interest rate, market, credit, management and the risk that a position could not be closed when most advantageous. Investing in derivatives could lead to losses that are greater than the amount invested. The Fund may make short sales of securities, which involves the risk that losses may exceed the original amount invested. The Fund may use leverage, which may exaggerate the effect of any increase or decrease in the value of securities in the Fund’s portfolio or the Fund’s net asset value, and therefore may increase the volatility of the Fund. Investments in foreign securities involve greater volatility and political, economic and currency risks and differences in accounting methods. These risks are increased for emerging markets. Investments in fixed-income instruments typically decrease in value when interest rates rise. The Fund will incur higher and duplicative costs when it invests in mutual funds, ETFs and other investment companies. There is also the risk that the Fund may suffer losses due to the investment practices of the underlying funds. For more information on these risks and other risks of the Fund, please see the Prospectus.

Investors should carefully consider the investment objectives, risks, charges and expenses of the Angel Oak Funds. This and other important information about each Fund is contained in the Prospectus or Summary Prospectus for each Fund, which can be obtained by calling 855-751-4324 or by visiting www.angeloakcapital.com. The Prospectus or Summary Prospectus should be read carefully before investing.

Index performance is not indicative of Fund performance. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Current performance can be obtained by calling 855-751- 4324.

The Angel Oak Funds are distributed by Quasar Distributors, LLC.

© 2025 Angel Oak Capital Advisors, which is the adviser to the Angel Oak Funds.